Hitler Answers Roosevelt

Source: http://ihr.org/other/HitlerAnswersRoosevelt

The German Leader's Reply to The American President's Public Challenge

Foreword

Of the many speeches made by Adolf Hitler during his lifetime, certainly one of the most important was his address of April 28, 1939. It was also very probably the most eagerly anticipated and closely followed speech of the time, with many millions of people around the world listening to it live on radio or reading of it the next day in newspapers.

American journalist and historian William L. Shirer, a harsh critic of the Third Reich who was reporting from Europe for CBS radio at the time, later described this Hitler speech as “probably the most brilliant oration he ever gave, certainly the greatest this writer ever heard from him.” The address is also important as a detailed, well-organized presentation of the German leader’s view of his country’s place in the world, and as a lucid review of his government’s foreign policy objectives and achievements during the first six years of his administration.

The speech was a response to a much-publicized message to Hitler – with a similar one to Italian leader Benito Mussolini – issued two weeks earlier by President Franklin Roosevelt. In it, the American leader issued a provocative challenge, calling on Hitler to promise that he would not attack 31 countries, which he named.

Made public on the evening of April 14, the president’s message was given wide attention in newspapers around the globe. Roosevelt and his inner circle anticipated that the American public would be pleased with his seeming concern for world peace, and expected that this much-publicized challenge would embarrass the German leader. Harold Ickes, a high-level official in the Roosevelt administration, praised the president’s message as “a brilliant move” that “has put both Hitler and Mussolini in a hole.”

Along with many other newspapers across the country, the daily Evening Star of Washington, DC, praised Roosevelt’s initiative, declaring in an editorial that “the overwhelming majority” of “Americans rejoice in their President’s constructive move for peace.” But not everyone was so impressed. Many regarded the message as arrogant and potentially dangerous meddling in foreign issues that did not involve any vital American interest, and which Roosevelt did not adequately understand. As US historian Robert Dallek has observed, the message strengthened the concerns of those who believed that the President was seeking to deflect attention from persistent problems at home by meddling abroad.

The influential Protestant journal, Christian Century, remarked that, in issuing his challenge, President Roosevelt “had taken his stand before the axis dictators like some frontier sheriff at the head of a posse.” An important Roman Catholic journal, Commonweal, regarded the message as one-sided, noting that it had ignored “the wrongs committed by post-war England and France, what they had contributed to the impoverishment of the Axis powers ...” British historian Leonard Mosley later characterized it as “ham-handed,” while German historian Joachim Fest called the message a piece of “naïve demagoguery.”

Because Roosevelt’s challenge had generated such broad international attention, the announcement a few days later that the German leader would respond to it in an address to a specially summoned session of the Reichstag in Berlin understandably increased interest in Hitler’s reply. Especially in the US and Europe, many people keenly anticipated the “second round” in this duel of words between two major world leaders.

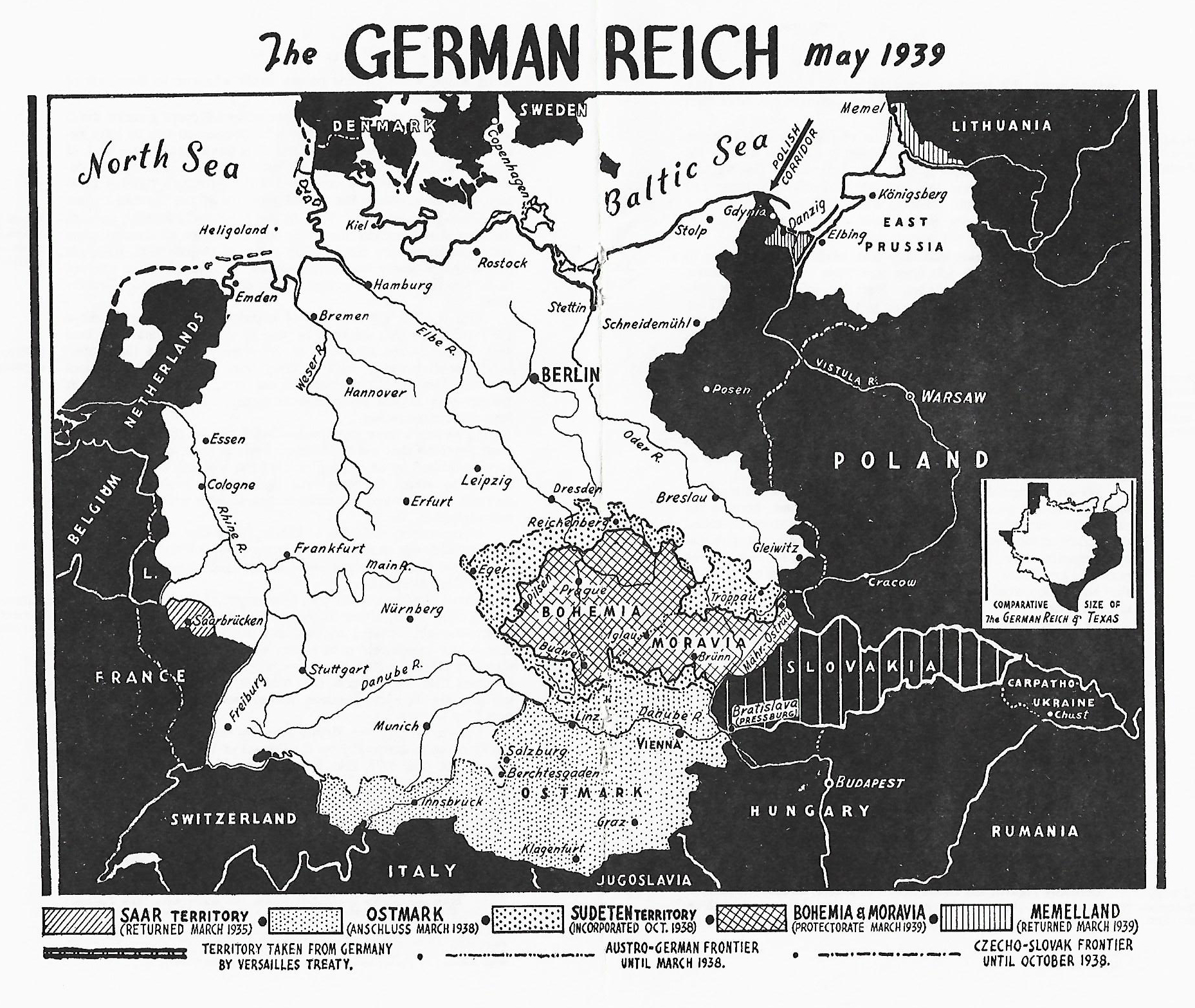

Dramatic recent developments in Europe and growing fear of a war involving the major European powers naturally heightened interest in what Hitler would say. Some months earlier, the ethnically German “Sudetenland” region of Czechoslovakia had been incorporated into the German Reich – which now also included Austria – in accord with the Munich Agreement of the “Four Power” leaders of Britain, France, Germany and Italy. Then, just a few weeks before Roosevelt sent his message to Hitler, Germany had surprised the world by suddenly taking control of the Czech lands, adding them to the Reich as the “Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia.” Especially in the US, influential newspapers, magazines and radio commentators portrayed Hitler’s takeover of Prague as an act of brazen aggression, one that proved that the German leader was so untrustworthy and insatiable that he must be regarded as a grave threat to peace and security. The German government’s recent demand that Poland permit Danzig to return to the Reich was widely cited as further evidence that Hitler threatened world peace.

Under these circumstances, Hitler naturally devoted considerable attention in his address to those topical issues and fears. But while it was meant for a global audience and readership, the German leader directed his speech above all to his own people.

Unlike Franklin Roosevelt, Hitler did not rely on speechwriters. The words he spoke were his own. To be sure, in preparing this address and similarly detailed speeches, he turned to various government officials and agencies for the statistics and other specific data he intended to cite. However, the ideas, arguments, turns of phrase, tone and structure of this address were entirely Hitler’s. In preparing the text of an important address, he would typically dictate a first draft to one or more secretaries, and then make revisions and changes until a satisfactory final text was produced – a process that could require considerable time and attention.

Broadcast on radio stations around the world, Hitler’s two-hour Reichstag address of Friday afternoon, April 28, was heard by millions of listeners. In the US, all three major radio networks broadcast it live, with running English-language translation. The next day, Hitler’s speech was the leading news item on the front page of every major American daily newspaper, and many published lengthy excerpts from it. “Interest in the speech surpasses anything so far known,” the German embassy in Washington reported to Berlin.

Astute observers realized that Roosevelt had greatly underestimated the shrewdness and rhetorical skill of the German leader. “Hitler had all the better of the argument,” remarked US Senator Hiram Johnson of California, a prominent “progressive” lawmaker. “Roosevelt put his chin out and got a resounding whack.” US Senator Gerald Nye commented simply, “He asked for it.”

James MacGregor Burns, a prominent American historian and an ardent admirer of Franklin Roosevelt, later wrote of the exchange: “While neither the President nor [US Secretary of State] Hull had been optimistic about the outcome, in his first widely publicized encounter with Hitler, Roosevelt had come off a clear second best.” John Toland, another well-regarded US historian, called Hitler’s response “a remarkable display of mental gymnastics.” The German leader “took up the President’s message point by point, demolishing each like a schoolmaster.”

In his carefully prepared address, the German leader largely succeeded in portraying the American president’s initiative as a pretentious and impertinent maneuver – one that, moreover, demonstrated a simplistic and superficial view of geopolitical realities, a skewed sense of justice, and a deficient understanding of history.

Although it was given prominent play in the US media, the attitude of the American press toward Hitler’s speech was generally dismissive and disparaging. Typical was the view of the Evening Star of Washington, DC. In an editorial, the influential daily denigrated the address as “crafty and cunning,” while New York City’s Brooklyn Eagle called it “rambling, confused.” Along with most US newspapers, the two dailies ignored the German leader’s plea for justice, equity and even-handedness, and the specifics of his detailed critique of Roosevelt’s message. Even more unfriendly than the attitude expressed in the editorial columns of the country’s newspapers was the snide, belittling and often viciously hostile portrayal of Hitler in editorial cartoons. By early 1939, most of the American media had adopted a scathing and belligerent attitude toward National Socialist Germany and its leader. Hitler was routinely portrayed as so malign and duplicitous that anything he said was simply not worthy of respectful or serious consideration.

This attitude was noted, for example, by the Polish ambassador in Washington, Jerzy Potocki. In a confidential dispatch of January 12, 1939, he reported to the Foreign Ministry in Warsaw:

To most discerning observers, it was obvious that the American president’s message was more a publicity stunt than a serious initiative for peace. For one thing, he addressed this appeal only to the leaders of Germany and Italy. He made no similar request to leaders in any other country. And given America’s own record of military intervention in foreign countries, it’s difficult to accept that Roosevelt himself actually believed his assertion that the only valid or justifiable reason why any country should go to war would be in “the cause of self-evident home defense.” Over the years, US forces have attacked numerous countries that presented no clear or present danger to the US, or any threat to vital American interests.

Roosevelt’s listing of countries that supposedly might be threatened by Germany is all the more remarkable given how events unfolded over the next few years. Finland, the first country on the President’s list, was in fact attacked seven months later – not by Germany, but rather by the Soviet Union. During World War II, Finland was an ally of Hitler’s Germany, while the Soviet Union was an important military partner of the US. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were the next countries on the President’s list. These three Baltic nations were subjugated by force in 1940 – not by German troops, but by the Red Army. Later during World War II, President Roosevelt accepted Stalin’s brutal incorporation of those three countries into the USSR.

Poland was also on the President’s list. But when Soviet troops attacked Poland from the East in September 1939, neither Britain, France nor the US did anything to counter the aggression. After Soviet forces took control of all of Poland in 1944-1945, the US accepted the Soviet subjugation of the country.

Britain and France were naturally also on Roosevelt’s list. But just a few months after his message to Hitler, those two countries went to war against Germany – with the leaders in London and Paris citing the German attack against Poland as their reason for the move. At least two countries on Roosevelt’s list – Syria and Palestine – were hardly in danger of attack by Germany, especially given that, as Hitler pointed out, they were already under military subjugation by “democratic” countries.

The President’s mention of Palestine in his message prompted a particularly sharp rejoinder by Hitler about British oppression of that country. Palestinians were enraged not only by Britain’s uninvited rule, he noted, but also by the support given by British leaders to the Jewish “interlopers” who were trying to impose Zionist control in their country. Roosevelt either knew nothing about the actual status of Palestine, or his supposed concern for its freedom was a sham. He was, of course, hardly the only American politician to support Zionist subjugation of Palestine while at the same time proclaiming his love of freedom and democracy.

Iran, the final country listed in the President’s message, was later invaded – but not by Germany. When British and Soviet forces attacked and occupied that neutral country in August 1941, President Roosevelt not only rejected a plea for help from Iran’s government, he justified and supported the brutal takeover of that country.

The cause of world peace, Roosevelt said in his message to Hitler, would be “greatly advanced” if world leaders were to provide “a frank statement relating to the present and future policy of governments.” This was sheer hypocrisy. During this period – months before the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939 – the President was himself covertly pressing for conflict against Germany.

At a secret meeting seven months earlier, he had told the British ambassador, Ronald Lindsay, that if Britain and France “would find themselves forced to war” against Germany, the United States would ultimately also join. Roosevelt went on to explain during their White House meeting on September 19, 1938, that it would require some clever maneuvering to make good on this pledge. The President went on to urge the envoy to persuade his government in London to impose an economic embargo against Germany with the hope and expectation that the German leadership would respond by openly going to war against Britain, which would then enable the US to join the anticipated war against Germany with a minimum of protest from the American public.

In November 1938, the Polish ambassador to Washington reported to Warsaw that William Bullitt, a high-level US diplomat and a particularly trusted colleague of President Roosevelt, had assured him that the US would “undoubtedly” enter a war against Germany, “but only after Great Britain and France had made the first move.” In January 1939, Polish ambassador Potocki reported on another confidential conversation with Bullitt, who assured him that the United States would be prepared “to intervene actively on the side of Britain and France in case of war” against Germany. Bullitt went on to confide that the US was ready to “place its whole wealth of money and raw materials at their disposal.”

A few weeks later, the Polish ambassador in Paris, Jules Lukasiewicz, confidentially informed Warsaw of a talk with William Bullitt, the US ambassador to France. The American envoy had assured him that if hostilities should break out, one could “foresee right from the beginning the participation of the United States in the war on the side of France and Britain.”

These pledges were kept secret because the President and his close advisors knew that American public opinion strongly opposed US involvement in another war in Europe. In that more trusting era, Americans believed their president to be sincere in his public assurances of the government’s peaceful intentions, and trusted his promise to keep their country out of any war that might break out in Europe.

The historic April 1939 exchange between Roosevelt and Hitler is important in helping to better understand the foreign policy outlook and goals of those two influential twentieth-century leaders, and how very differently each viewed recent history and his own country’s role in the world.

Their exchange was highlighted in the US government’s widely-viewed World War II “Why We Fight” film series. It showed Hitler reading the list of countries that allegedly were threatened with attack or invasion by Germany, to which the Reichstag audience responded – at first with silence and then with laughter. The narrator told viewers that Hitler treated the President’s public challenge as a “huge joke.” In fact, the audience laughed because they quite understandably regarded as ludicrous the notion that German forces might attack or invade such countries as Spain, Ireland, Syria or Iran.

Far from regarding it as a “huge joke,” Hitler made an effort to respond to every point of the President’s telegram. Roosevelt, for his part, declined to reply to Hitler’s detailed address, much less respond to the German leader’s specific points. Roosevelt ignored even Hitler’s appeal to the US government to fulfill the solemn pledges it had made twenty years earlier to Germany and the world.

In the months that followed, American policy toward Germany became increasingly hostile. In 1940 and 1941 the President sought ever more openly to persuade the skeptical American public to support Britain and Soviet Russia in war against Germany. The worsening US-German relations culminated in Hitler’s Reichstag address of December 11, 1941 – four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and the mutual declarations of war of those two countries – in which he reviewed the record of America’s increasingly overt acts of aggression against Germany. After stating that his patience with US belligerency and lawlessness had finally reached an end, Hitler announced that his nation was now joining Japan in war against the United States.

Here below is the full text of President Roosevelt’s April 1939 message to Hitler, followed by a specially prepared translation of the complete text of the Reichstag address by the German leader in response. Endnotes have been added to provide context and to help to clarify unfamiliar references. A list of items for suggested further reading is also provided.

Mark Weber, October 2020

President Roosevelt’s Message

The following is the text of the message sent by President Roosevelt to Chancellor Adolf Hitler on April 14, 1939

You realize, I am sure, that throughout the world hundreds of millions of human beings are living today in constant fear of a new war or even a series of wars.

The existence of this fear — and the possibility of such a conflict-are of definite concern to the people of the United States for whom I speak, as they must also be to the peoples of the other nations of the entire Western Hemisphere. All of them know that any major war, even if it were to be confined to other continents, must bear heavily on them during its continuance and also for generations to come.

Because of the fact that after the acute tension in which the world has been living during the past few weeks there would seem to be at least a momentary relaxation — because no troops are at this moment on the march — this may be an opportune moment for me to send you this message.

On a previous occasion I have addressed you in behalf of the settlement of political, economic, and social problems by peaceful methods and without resort to arms.

But the tide of events seems to have reverted to the threat of arms. If such threats continue, it seems inevitable that much of the world must become involved in common ruin. All the world, victor nations, vanquished nations, and neutral nations, will suffer.

I refuse to believe that the world is, of necessity, such a prisoner of destiny. On the contrary, it is clear that the leaders of great nations have it in their power to liberate their peoples from the disaster that impends. It is equally clear that in their own minds and in their own hearts the peoples themselves desire that their fears be ended.

It is, however, unfortunately necessary to take cognizance of recent facts.

Three nations in Europe and one in Africa have seen their independent existence terminated. A vast territory in another independent Nation of the Far East has been occupied by a neighboring State. Reports, which we trust are not true, insist that further acts of aggression are contemplated against still other independent nations. Plainly the world is moving toward the moment when this situation must end in catastrophe unless a more rational way of guiding events is found.

You have repeatedly asserted that you and the German people have no desire for war. If this is true there need be no war.

Nothing can persuade the peoples of the earth that any governing power has any right or need to inflict the consequences of war on its own or any other people save in the cause of self-evident home defense.

In making this statement we as Americans speak not through selfishness or fear or weakness. If we speak now it is with the voice of strength and with friendship for mankind. It is still clear to me that international problems can be solved at the council table.

It is therefore no answer to the plea for peaceful discussion for one side to plead that unless they receive assurances beforehand that the verdict will be theirs, they will not lay aside their arms. In conference rooms, as in courts, it is necessary that both sides enter upon the discussion in good faith, assuming that substantial justice will accrue to both; and it is customary and necessary that they leave their arms outside the room where they confer.

I am convinced that the cause of world peace would be greatly advanced if the nations of the world were to obtain a frank statement relating to the present and future policy of governments.

Because the United States, as one of the Nations of the Western Hemisphere, is not involved in the immediate controversies which have arisen in Europe, I trust that you may be willing to make such a statement of policy to me as head of a Nation far removed from Europe in order that I, acting only with the responsibility and obligation of a friendly intermediary, may communicate such declaration to other nations now apprehensive as to the course which the policy of your government may take.

Are you willing to give assurance that your armed forces will not attack or invade the territory or possessions of the following independent nations: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, The Netherlands, Belgium, Great Britain and Ireland, France, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, Russia, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Iraq, the Arabias, Syria, Palestine, Egypt and Iran.

Such an assurance clearly must apply not only to the present day but also to a future sufficiently long to give every opportunity to work by peaceful methods for a more permanent peace. I therefore suggest that you construe the word “future” to apply to a minimum period of assured non-aggression – ten years at the least, a quarter of a century, if we dare look that far ahead.

If such assurance is given by your government, I shall immediately transmit it to the governments of the nations I have named and I shall simultaneously inquire whether, as I am reasonably sure, each of the nations enumerated will in turn give like assurance for transmission to you.

Reciprocal assurances such as I have outlined will bring to the world an immediate measure of relief.

I propose that if it is given, two essential problems shall promptly be discussed in the resulting peaceful surroundings, and in those discussions the government of the United States will gladly take part.

The discussions which I have in mind relate to the most effective and immediate manner through which the peoples of the world can obtain progressive relief from the crushing burden of armament which is each day bringing them more closely to the brink of economic disaster.

Simultaneously the government of the United States would be prepared to take part in discussions looking toward the most practical manner of opening up avenues of international trade to the end that every Nation of the earth may be enabled to buy and sell on equal terms in the world market as well as to possess assurance of obtaining the materials and products of peaceful economic life.

At the same time, those governments other than the United States which are directly interested could undertake such political discussions as they may consider necessary or desirable.

We recognize complex world problems which affect all humanity but we know that study and discussion of them must be held in an atmosphere of peace. Such an atmosphere of peace cannot exist if negotiations are overshadowed by the threat of force or by the fear of war.

I think you will not misunderstand the spirit of frankness in which I send you this message. Heads of great governments in this hour are literally responsible for the fate of humanity in the coming years. They cannot fail to hear the prayers of their peoples to be protected from the foreseeable chaos of war. History will hold them accountable for the lives and the happiness of all – even unto the least.

I hope that your answer will make it possible for humanity to lose fear and regain security for many years to come.

A similar message is being addressed to the Chief of the Italian government.

Chancellor Hitler's Speech

The following is the text of the address delivered by Chancellor Hitler on April 28, 1939, at a specially summoned session of the German Reichstag.

Members of the German Reichstag!

The President of the United States of America has addressed a telegram to me, the curious contents of which you are already familiar. Before I, the addressee, actually received this document, the rest of the world had already been informed of it by radio and newspaper reports. Numerous commentaries in the organs of the democratic world press had already happily enlightened us as to the fact that this telegram was a tactically clever document, designed to impose upon the states, in which the people govern, the responsibility for the warlike measures adopted by the plutocratic countries.

Therefore I decided to summon the German Reichstag so that you, as Reichstag deputies, would have the opportunity to be the first to hear my answer, and of either confirming or rejecting it. In addition, I also considered it appropriate to act in accord with the method of procedure chosen by President Roosevelt and, for my part, to inform the rest of the world of my answer in our own way. I also wish to use this occasion to give expression to the feelings with which the tremendous historical happenings of the month of March inspire me. I can express my deepest feelings only in the form of humble thanks to Providence which called upon me, and permitted me, once an unknown soldier of the [world] war [of 1914-1918], to rise to be the Leader of my people, so dear to me.

Providence showed me the way to free our people from the depths of its misery without bloodshed and to lead it upward once again. Providence granted that I might fulfill my life’s task to raise my German people from of the depths of defeat and to liberate it from the bonds of the most outrageous dictate of all times. That alone has been the goal of my efforts.

Since the day on which I entered political life, I have lived for no other idea than that of winning back the freedom of the German nation, restoring the power and strength of the Reich, overcoming the internal discord of our people, repairing its isolation from the rest of the world, and safeguarding the maintenance of its independent economic and political life.

I have intended only to restore that which others once broke by force. I have desired only to make good that which satanic malice or human stupidity destroyed or ruined. I have, therefore, taken no step that violated the rights of others, but have only restored the right that was violated twenty years ago.

The Greater German Reich today contains no territory that was not from the earliest times a part of this Reich, bound up with it, or subject to its sovereignty. Long before an American continent had been discovered – not to say settled – by white people, this Reich existed, not merely with its present extent, but with many additional regions and provinces that have since been lost.

Twenty-one years ago, when the bloodshed of the [First World] war came to an end, millions of minds were filled with the ardent hope that a peace of reason and justice would reward and bless the nations that were hostages of the fearful scourge of the [First] World War. I say “reward,” for all those men and women – whatever the conclusions arrived at by historians – bore no responsibility for these fearful happenings. In some countries there may still be politicians who even at that time might be considered responsible for that most horrible slaughter of all times, but the great mass of fighting soldiers of every country and nation were by no means guilty, but rather deserving of pity.

Hitler is saluted at this special session of the German Reichstag on April 28, 1939. On this occasion, the Chancellor delivered a widely anticipated address in response to a much-publicized challenge by American president Franklin Roosevelt. Millions around the world listened on radio to Hitler’s two hour speech as he delivered it. In the US, all three major radio networks broadcast it live, with running English-language translation. The next day, it was the leading news item on the front page of every major American daily newspaper.

As you know, I myself had never played a part in politics before the war. Like millions of others, I only carried out such duties as I was called upon to fulfill as a decent citizen and soldier. It was therefore with an absolutely clear conscience that I was able to take up the cause of the freedom and future of my people, both during and after the war. And I can therefore speak in the name of millions and millions of others who are equally blameless when I declare that all those, who had only fought for their nation in loyal fulfillment of their duty, were entitled to a peace of reason and justice, so that humanity might at last set to work to make good by joint effort the losses which all had suffered.

But those millions were cheated of that peace; for not only did the German people, and the other peoples fighting on our side suffer through the peace treaties, but these treaties had a destructive impact on the victors as well.

That politics should be controlled by men who had not themselves fought in the war was recognized for the first time as a misfortune. Hatred was unknown to the soldiers, but not to those elderly politicians who had carefully preserved their own precious lives from the horrors of war, and who now descended upon humanity in the guise of insane spirits of revenge.

Hatred, malice and unreason were the intellectual forebears of the dictated Treaty of Versailles. [1] Territories and states with a history going back a thousand years were arbitrarily broken up and dissolved. People who have belonged together since time immemorial were torn asunder; economic conditions of life were ignored, while the peoples themselves were dealt with as victors and vanquished, as masters possessing all rights or as slaves possessing none.

That document of Versailles has fortunately been set down in black and white for generations to come, for otherwise it would have been regarded in the future as the grotesque product of a wild and corrupt imagination. Nearly 115 million people were robbed of their right of self-determination, not by victorious soldiers, but by mad politicians, and were arbitrarily removed from ancient communities and made part of new ones without any consideration of blood, ancestry, common sense, or the economic conditions of life.

The results were appalling. Though at that time the statesmen were able to destroy a great many things, there was one factor which could not be eliminated; the gigantic mass of people living in Central Europe, crowded together in a confined area, can only secure their daily bread by the maximum of labor and resultant order.

But what did these statesmen of the so-called democratic empires know of these problems? A flock of utterly stupid and ignorant people was let loose on humanity. In areas in which about 140 people per square kilometer have to gain a livelihood, they simply destroyed the order that had been built up over nearly two thousand years of historical development, and created disorder, without themselves being capable or desirous of solving the problems confronting the communal life of these people – for which, moreover, as dictators of the new world order, they had at that time assumed responsibility.

However, when this new world order turned out to be a catastrophe, the democratic peace dictators, both American and European, were so cowardly that none of them ventured to take the responsibility for what occurred. Each put the blame on the others, thus endeavoring to save himself from the judgment of history. However, the people who were mistreated by their hatred and lack of reason were, unfortunately, not in a position to join them in that exit.

It is impossible to enumerate the stages of our own people’s sufferings. Robbed of the whole of its colonial possessions, 2 deprived of all its financial resources, plundered by so-called reparations, and thus impoverished, our nation was driven into the darkest period of its national misfortune. And it should be noted that this was not National Socialist Germany, but democratic Germany 3 – the Germany which was weak enough to trust even for a single moment the promises of democratic statesmen.

The resulting misery and continuing impoverishment began to bring our nation to political despair. Even decent and industrious people of Central Europe looked to the possibility of deliverance in the complete destruction of the old order, which to them represented a curse.

Jewish parasites, on the one hand, plundered the nation ruthlessly and, on the other hand, incited the people, reduced as it was to misery. As the misfortune of our nation became the aim and object of that race, it was possible to breed among the growing army of unemployed suitable elements for the Bolshevik revolution.

The decay of political order and the confusion of public opinion by an irresponsible Jewish press led to ever stronger shocks to economic life, and consequently to increasing misery and to greater readiness to accept subversive Bolshevik ideas. The army of the Jewish world revolution, as the army of unemployed was called, finally rose to almost seven million.

Germany had never before known such conditions. In the area in which this great people and the old Habsburg states belonging to it lived, economic life, despite all the difficulties of the struggle for existence involved by the excessive density of population, had not become more uncertain in the course of time but, on the contrary, more and more secure.

Industriousness and diligence, great thrift, and a love of scrupulous order, though they did not enable the people in this territory to accumulate excessive riches, did at any rate insure them against abject misery. The results of the wretched peace forced upon them by the democratic dictators were thus all the more terrible for these people, who were condemned at Versailles. Today we know the reason for this frightful outcome of the [First] World War.

Primarily, it was the greed for spoils. That which seldom pays in private life, could, they believed, when enlarged a million-fold, be represented to mankind as a profitable experiment. If large nations were plundered and the utmost squeezed out of them, it would then be possible to live a life of carefree idleness. Such was the opinion of these economic dilettantes.

To that end, first of all, the states themselves had to be dismembered. Germany had to be deprived of her colonial possessions, although, they were without any value to the imperial democracies; the most important [German] regions of natural resources had to be invaded and – if necessary – placed under the influence of the democracies; and above all, the unfortunate victims of that democratic mistreatment of nations and people had to be prevented from ever recovering, let alone rising against their oppressors.

Thus was concocted the satanic plan to burden generations with the curse of those dictates. For 60, 70, or 100 years, Germany was to pay sums so exorbitant that the question of how they were actually to be raised must forever remain a mystery. To raise such sums in gold, in foreign currency, or by way of regular payments in kind, would have been absolutely impossible without the bedazzled collectors of this tribute being ruined as well.

As a matter of fact, these democratic peace dictators basically destroyed the world economy with their Versailles madness. 4 Their senseless dismemberment of peoples and states led to the destruction of common production and trade interests which had become well established in the course of hundreds of years, thereby forcing the development of autarchic tendencies, and with it the destruction of the previous general conditions of the world economy.

Twenty years ago, when I signed my name in the book of political life as the seventh member of the then German Workers Party 5 in Munich, I saw the impact of those signs of decay all around me. The worst of it – as I have already emphasized – was the utter despair of the masses that resulted therefrom, the disappearance among the educated classes of all confidence in human reason, let alone in a sense of justice, and a predominance of brutal selfishness among all such egotistically inclined creatures.

The extent to which, in the course of what is now twenty years, I have been able to mold a nation from such chaotic disorganization into an organic whole and to establish a new order, is already part of German history.

What I wish to make clear today, by way of introduction, is above all the goals of my political outlook and their realization with regard to foreign policy.

One of the most shameful acts of oppression ever committed is the dismemberment of the German nation and the political disintegration, provided for in the Dictate of Versailles, of the area in which it had, after all, lived for thousands of years.

I have never, my Reichstag deputies, left any doubt that in point of fact it is scarcely possible anywhere in Europe to arrive at an entirely satisfactory harmony of state and ethnic boundaries that would be satisfactory to everyone concerned. On the one hand, the migration of peoples that gradually came to a standstill during the last few centuries, and on the other, the development of large communities, have brought about a situation which, whatever way they look at it, will necessarily be considered unsatisfactory in in some way or other by those concerned. It was, however, precisely the way in which these ethnic-national and political developments were gradually stabilized in the last century that led many to cling to the hope that in the end a compromise would be found between respect for the national life of the various European peoples and the recognition of established political structures – a compromise by which, without destroying the political order in Europe and with it the existing economic basis, nationalities could nevertheless be preserved.

Those hopes were destroyed by the [First] World War. The peace dictate of Versailles did justice neither to the one principle nor to the other. Neither the right of self-determination was respected, nor was consideration given to the political, let alone the economic necessities and conditions, for European development. Nevertheless, I have never denied that – as I have already emphasized – there would have to be limits even to a revision of the Treaty of Versailles. And I have always said so with the utmost frankness – not for any tactical reasons, but from my innermost conviction. As the national leader of the German people, I have never left any doubt that, wherever the higher interests of the European community are at stake, specific national interests must, if necessary, be relegated to second place.

And – as I have already emphasized – this is not for tactical reasons, for I have never left any doubt that I am absolutely in earnest in this attitude. With regard to many territories that might possibly be disputed, I have, therefore, come to final decisions, which I have proclaimed not only to the outside world, but also to my own people, and I have seen to it that those decisions are respected.

I have not, as France did in 1870-1871, 6 described the cession of Alsace-Lorraine as intolerable for the future. Instead, I here made a distinction between the Saar territory and these two former Reich provinces. And I have never changed my attitude, nor will I ever do so. I have not allowed this attitude to be modified or prejudiced inside the country on any occasion, either in the press or in any other way. The return of the Saar territory 7 has done away with all territorial problems in Europe between France and Germany. I have, however, always regarded it as regrettable that French statesmen have taken that attitude for granted. That’s not the way to look at the matter. It was not because of fear of France that I expressed this attitude. As a former soldier, I see no reason whatsoever for any such fear. Moreover, as regards the Saar territory I made it quite clear that we would not countenance any refusal to return it to Germany.

No, I have confirmed this attitude toward France as an expression of appreciation of the need to attain peace in Europe, instead of sowing the seed of continual uncertainty and even tension by making unlimited demands and continually asking for revision. If this tension has nevertheless now arisen, the responsibility does not lie with Germany but with those international elements that systematically promote such tension in order to serve their capitalist interests.

I have made binding declarations to a large number of states. None of those states can complain that even a trace of a demand contrary thereto has ever been made of them by Germany. No Scandinavian statesman, for example, can claim that a request has ever been put to him by the German government or by German public opinion that is incompatible with the sovereignty or integrity of his country.

I was pleased that a number of European states availed themselves of these declarations by the German government to express and emphasize their desire, as well, for absolute neutrality. This applies to Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, and so forth. I have already mentioned France. I need not mention Italy, with which we are united in the deepest and closest friendship, nor Hungary and Yugoslavia, with whom, as neighbors, our relations are fortunately of the friendliest.

Furthermore, I have left no doubt from the first moment of my political activity that there existed other circumstances that represent so mean and gross an outrage of the right of self-determination of our people that we can never accept or endorse them. I have never written a single line or made a single speech displaying a different attitude towards the states just mentioned. Moreover, with reference to the other cases, I have never written a single line or made a single speech in which I have expressed any attitude contrary to my actions.

One. Austria, the oldest eastern march [Ostmark] of the German people, was once the buttress of the German Nation on the south-east of the Reich. The Germans of that country are descended from settlers from all the German tribes, even though the Bavarian tribe contributed the major portion. Later this Ostmark became the foundation of a centuries-old imperial realm, with Vienna as the capital of the German Reich of that period.

That German Reich was finally broken up in the course of a gradual dissolution by Napoleon, the Corsican, but continued to exist as a German federation, and not so long ago fought and suffered in the greatest war of all time as a political entity that was the expression of the national feelings of the people, even if it was no longer one united state. I myself am a child of that Ostmark.

Not only was the German Reich beaten down and Austria broken up into its component parts by the criminals of Versailles, but Germans were also forbidden to acknowledge that community to which they had declared their adherence for more than a thousand years. I have always regarded the elimination of this state of affairs as the greatest and most sacred task of my life. I have never failed to proclaim this determination, and I have always been resolved to realize these ideas that haunted me day and night.

I would have sinned against my call by Providence had I failed in my own endeavor to lead my native country and my German people of the Ostmark back to the Reich, 8 and thus to the national community of the German people. In doing so, moreover, I have erased the most disgraceful page of the Treaty of Versailles. I have established the right of self-determination once again, and have done away with the democratic countries’ oppression of seven and a half million Germans. I have lifted the ban that prevented them from voting on their own fate, and carried through the historic referendum. The result was not only what I had expected, but also precisely what had been anticipated by the Versailles democratic oppressors of nations. For why else had they forbidden a referendum on the question of Union. [Anschluss]

Two. Bohemia and Moravia. When in the course of the migrations of peoples Germanic tribes began, for reasons inexplicable to us, to migrate out of the territory that today is Bohemia and Moravia, a foreign Slavic people made its way into this territory, and made a place for itself amongst the remaining Germans. Since that time the area occupied by this Slavic people has been enclosed in the form of a horseshoe by Germans.

From an economic point of view an independent existence is, in the long run, impossible for these lands except in the context of a close relationship with the German nation and the German economy. But apart from that, nearly four million Germans lived in this territory of Bohemia and Moravia. A policy of national annihilation that set in, particularly after the Treaty of Versailles, under pressure of the Czech majority, combined, too, with economic conditions and the rising tide of distress, led to some emigration of those German, so that the Germans left in the territory were reduced to approximately 3,700,000. The population of the fringe of the territory is uniformly German, but there are also large German linguistic enclaves in the interior.

The Czech nation is in its origin foreign to us, but in the thousand years in which the two peoples have lived side by side, Czech culture has been significantly formed and molded by German influences. The Czech economy is the result of its connection with the greater German economic system. The capital of this country [Prague] was for a time a German imperial city, and it has the oldest German university. 9 Numerous cathedrals, city halls, and residences of nobles and citizens alike bear witness to the German cultural influence.

The Czech people itself has in the course of centuries alternated between close and more distant relations with the German people. Every close contact resulted in a period in which both the German and the Czech nations flourished; every estrangement was calamitous in its consequences.

We are familiar with the merits and values of the German nation, but the Czech nation, with the sum total of its skill and ability, its industry, its diligence, its love of its native soil, and of its own national heritage, also deserves our respect. In fact, there were periods when this mutual respect for the qualities of the other nation was a matter of course.

The democratic peacemakers of Versailles can take the credit for having assigned to the Czech people the special role of a satellite state, which could be used against Germany. For this purpose they arbitrarily adjudicated foreign national property to the Czech state, which was utterly incapable of survival on the strength of the Czech national unit alone. That is, they did violence to other nationalities in order to secure a basis for a state that was to be a latent threat to the German nation in Central Europe.

For this state [Czechoslovakia], in which the so-called predominant national element was actually in the minority, could be maintained only by means of a brutal violation of the national units that made up the majority of the population. 10 This violation was possible only in so far as protection and assistance were granted by the European democracies. This assistance could naturally be expected only on condition that this state was prepared loyally to adopt and play the role which had been assigned to at birth. But the purpose of this role was none other than to prevent the consolidation of Central Europe, to provide a bridge into Europe for Bolshevik aggression, and above all to act as a mercenary of the European democracies against Germany.

Everything then followed automatically. The more this state tried to fulfill the task it had been set, the greater was the resistance put up by the national minorities. And the greater the resistance, the more necessary it became to resort to oppression. This inevitable heightening of the inner contradictions led in its turn to an increased dependence on the European democratic founders and benefactors of the state, for they alone were in a position to maintain in the long run the economic existence of this unnatural and artificial creation. Germany was primarily interested in one thing only, namely, to liberate the nearly four million Germans in this country from their intolerable situation, and to make it possible for their return to their home country and to the thousand-year-old Reich.

It was only natural that this problem immediately brought up all the other aspects of the nationalities problem. It was also natural that the withdrawal of the different national groups would deprive what was left of the state of all capacity to survive – a fact of which the founders of the state had been well aware when they planned it at Versailles. It was for this very reason that they had decided to do violence on the other minorities, and forced these against their will to become part of this amateurishly constructed state.

I have, moreover, never left any doubt about my opinion and attitude on this matter. It is true that, as long as Germany herself was powerless and defenseless, this oppression of almost four million Germans could be carried out without the Reich offering any practical resistance. However, only a child in politics could have believed that the German nation would remain forever in the condition that it was in 1919. Only as long as the international traitors, supported from abroad, held the control of the German state, could one be sure of these disgraceful conditions being patiently tolerated. From the moment when, after the victory of National Socialism, these traitors had to transfer their domicile to the place from where they had received their subsidies, the solution of this problem was only a question of time. Moreover, this was exclusively a matter involving the nationalities concerned, and not one concerning Western Europe.

It was certainly understandable that Western Europe was interested in the artificial state that had been created for its interests. But that the nations surrounding this state should regard those interests as a determining factor for them was a false conclusion, which some may perhaps have regretted. In so far as those interests involved only the financial establishment of that state, Germany would have had no objection. But those financial interests were, in the final analysis, also entirely subordinate to the power-political goals of the democracies.

The financial assistance given too this state was guided by a single consideration, namely creation of a state armed to the teeth that could be a valuable bastion extending into the German Reich, which could constitute a basis for military operations in connection with invasions of the Reich from the west, or at any rate serve as an air base.

What was expected from this state is shown most clearly by the observation of the French Air Minister, M. Pierre Cot, who calmly stated 11 that the function of this state in case of any conflict was to be an air base for the landing and taking off of bombers, from which it would be possible to destroy the most important German industrial centers in a few hours. It is, therefore, understandable that the German government for its part decided to destroy this air base for bombers. It did not come to this decision out of hatred of the Czech people. Quite the contrary. For in the course of the thousand years during which the German and Czech peoples have lived together, there were often periods of close cooperation lasting hundreds of years, interrupted, to be sure, by only short periods of tension. In such periods of tension the passions of the people struggling with each other on their ethnic front lines can very easily dim the sense of justice, and thus give a false general picture. That’s a feature of every war. Only during the long epochs of living together in harmony did the two peoples agree that they were both entitled to make a sacred claim for regard and respect for their nationality.

In these years of struggle my own attitude towards the Czech people has been solely confined to the guardianship of national and Reich interests, combined with feelings of respect for the Czech people. One thing is certain however. Even if the democratic midwives of this state had succeeded in attaining their ultimate goal, the German Reich would certainly not have been destroyed, although we might have sustained heavy losses. No, the Czech people, by reason of its limited size and its position, would presumably have had to endure much more terrible, and indeed – I am convinced – catastrophic consequences.

I am happy that it has proved possible, even if to the annoyance of democratic interests, to prevent such a catastrophe in Central Europe, thanks to our own moderation and also to the good judgment of the Czech people. That which the best and wisest Czechs have struggled for decades to attain, is as a matter of course granted to this people in the National Socialist German Reich – namely, the right to their own nationality and the right to foster this nationality and to revive it. National Socialist Germany has no notion of ever betraying the ethnic-racial principles of which we are proud. They are beneficial not only to the German nation, but to the Czech people as well. What we demand is the recognition of a historical necessity and of an economic exigency in which we all find ourselves. When I announced the solution of this problem in the Reichstag on February 22, 1938, I was convinced that I was obeying the necessity of a Central European situation.

Even in March 1938, I still believed that by means of a gradual evolution it might prove possible to solve the problem of minorities in this state and, at one time or another, by means of mutual cooperation to arrive at a common understanding that would be advantageous to all interests concerned, politically as well as economically.

It was only after Mr. Benes, who was completely in the hands of his democratic international financiers, turned the problem into a military one and unleashed a wave of suppression over the Germans, while at the same time attempting by that mobilization of which you all know, 12 to inflict an international defeat on the German state, and to damage its prestige, that it became clear to me that a solution by those means was no longer possible. For the false report at that time of a German mobilization was quite obviously inspired from abroad and suggested to the Czechs in order to cause the German Reich such a loss of prestige.

I do not need to repeat again that in May of the past year Germany had not mobilized one single man, although we were all of the opinion that the very fate of Mr. Schuschnigg 13 should have shown all others the advisability of working for mutual understanding by means of a more just treatment of national minorities.

I for my part was at any rate prepared to attempt this kind of peaceful development with patience, though, if need be, the process might last some years. However, it was exactly such a peaceful solution that was a thorn in the flesh of the agitators in the democracies.

They hate us Germans and would prefer to eradicate us completely. What do the Czechs mean to them? They are nothing but means to an end. And what do they care for the fate of that small and valiant nation? What concern to they have for the lives of hundreds of thousands of brave soldiers who would have been sacrificed for their policy?

These Western European peace-mongers were not concerned to work for peace but to cause bloodshed so as in that way to set the nations against one another and thus cause still more blood to flow. For this reason they invented the story of German mobilization and misled Prague public opinion with it. It was intended to provide an excuse for the Czech mobilization; and then by this means they hoped to be able to exert the desired military pressure on the elections in Sudeten Germany 14 which could no longer be avoided.

In their view there remained only two alternatives for Germany: Either to accept this Czech mobilization and with it a disgraceful blow to her prestige, or to settle accounts with Czechoslovakia. This would have meant a bloody war, perhaps entailing the mobilization of the peoples of Western Europe, who had no interest in these matters, thereby involving them in the inevitable bloodlust and immersing humanity in a new catastrophe in which some would have the honor of losing their lives and others the pleasure of making war profits.

You are acquainted, gentlemen, with the decisions I quickly made at the time:

- To solve this question and, what’s more, by October 2, 1938, at the latest.

- To prepare this solution by all the means required to leave no doubt that any attempt at intervention would be met by the united force of the whole nation.

It was then that I decreed and ordered the strengthening of our western fortifications. 15 By September 25, 1938, they were already in such a condition that their defensive strength was thirty to forty times greater than that of the old “Siegfried Line” of the [First World] War. They are now mostly completed, and right now are being extended with new defense lines outside of Aachen and Saarbrücken, which I ordered later. These, too, are very largely ready for defense. Considering the scale of these, the greatest fortifications ever constructed, the German nation can feel perfectly assured that no power in this world will ever succeed in breaking through that front.

When the first provocative attempt at utilizing the Czech mobilization had failed to produce the desired result, the second phase began, in which the motives underlying a question that really concerned Central Europe alone, became all the more obvious.

If the cry of “Never another Munich” is raised in the world today, this simply confirms the fact that those warmongers regarded the peaceful solution of the problem to be the most pernicious thing that ever happened. They are sorry no blood was shed – not their blood, to be sure – for these agitators are, of course, never to be found where shots are being fired, but rather where money is being made. No, it would be the blood of many nameless soldiers!

Moreover, there would have been no need for the Munich Conference, 16 for that conference was only made possible by the fact that the countries which had at first incited those concerned to resist at all costs, were compelled later on, when the situation pressed for a solution in one way or another, to try to secure for themselves a more or less respectable retreat; for without Munich – that is to say, without the interference of the countries of Western Europe – a solution of the entire problem, if it had grown so acute at all, would very likely have been the easiest thing in the world.

The Munich decision led to the following results:

- One. The return to the Reich of the most essential parts of the [ethnic] German border settlements in Bohemia and Moravia. 17

- Two. The keeping open of the possibility of a solution of the other problems of that state – that is, a return and separation, respectively, of the existing Hungarian and Slovak [ethnic] minorities;

- Three. The guarantee question still remained open. As far as Germany and Italy were concerned, a guarantee of [the continued existence of] that state [Czechoslovakia] had, from the outset, been made dependent upon the consent of all interested parties bordering on that state – that is to say, contingent on the actual solution of problems concerning the parties mentioned, which were still unsolved.

The following problems were still left open:

- The return of the Magyar [ethnically Hungarian] districts to Hungary;

- The return of the [ethnically] Polish districts to Poland;

- The solution of the Slovak question;

- The solution of the [ethnic] Ukrainian question.

As you know, the negotiations between Hungary and Czechoslovakia had scarcely begun when both the Czechoslovakian and the Hungarian negotiators made a request to Germany and Italy, a country that stands side by side with Germany, to act as arbitrators in determining the new borders between Slovakia, the Carpatho-Ukraine and Hungary. 18 The countries concerned did not avail themselves of the opportunity of appealing to the Four Powers. On the contrary, they expressly renounced that opportunity – that is, they declined it. And that was quite understandable. All the people living in this area desired peace and quiet. Italy and Germany were prepared to answer the call. Neither Britain nor France raised any objection to this arrangement, even though it constituted a formal departure from the Munich Agreement. Nor could they have done so. It would have been madness for Paris or London to have protested against an action on the part of Germany or Italy, which had been undertaken solely at the request of the countries concerned.

The arbitration decision arrived at by Germany and Italy proved – as always happens in such cases – entirely satisfactory to neither party. From the outset the difficulty was that it had to be accepted voluntarily by both [affected] parties. As the arbitration decision was being put into effect, the two states quickly raised strong objections after having accepted it. Hungary, prompted by both general and specific interests, demanded the Carpatho-Ukraine region, 19 while Poland demanded a common border with Hungary. It was clear that, under such circumstances, even the remnant of the state that Versailles had brought into being was doomed.

In fact, perhaps only a single country was interested in the preservation of the earlier situation, and that was Romania. The man best authorized to speak on behalf of that country told me personally how desirable it would be to have a direct connection with Germany, perhaps by way of Ukraine and Slovakia. I mention this as an indication of the feeling of being menaced by Germany that the Romanian government – according to American clairvoyants – was supposed to be suffering.

It was now clear that Germany could not undertake the task of permanently opposing a development, much less to fight to maintain a state of affairs, for which we would never have made ourselves responsible. Thus, the stage had been reached at which I decided to make a declaration in the name of the German government, to the effect that we had no intention of any longer incurring any further reproach by opposing the common wishes of Poland and Hungary with regard to their borders, simply in order to keep open a road of approach for Germany to Romania.

Since, moreover, the Czech government resorted once more to its old methods, and Slovakia also gave expression to its desire for independence, 20 the further maintenance of the state was now out of the question. Czechoslovakia as constructed at Versailles had had its day. It collapsed not because Germany desired its breakup, but because in the long run it is impossible to create and sustain artificial states at the conference table, for they are incapable of survival. 21 A few days before the dissolution of that state, in response to an inquiry by Britain and France regarding a guarantee [of the existence of Czechoslovakia], Germany therefore refused to give such a guarantee, because all the conditions for it laid down at Munich no longer existed.

On the contrary, after the entire structure of the state had begun to break up and had already practically dissolved, the German government also finally decided to intervene. It did so only in fulfillment of an obvious duty. In that regard, the following should be noted: On the occasion of the first visit to Munich of the Czech Foreign Minister, Mr. Chvalkovsky, 22 the German government plainly expressed its views on the future of Czechoslovakia. I myself assured Mr. Chvalkovsky on that occasion that provided that the large [ethnic] German minority remaining in Czechia was fairly treated, and provided that a general settlement throughout the state were achieved, we would pledge a supportive attitude on Germany’s part, and would assuredly place no obstacles in the way of the state.

But I also made it clear beyond all doubt that if Czechia was to take any steps in line with the policies of the former president, Dr. Benes, Germany would not put up with any developments along such lines, but would nip them in the bud. I also pointed out at the same time that the maintenance of such a tremendous military arsenal in Central Europe for no reason or purpose could only be regarded is a source of danger.

Later developments proved how justified my warning had been. A continually rising tide of underground propaganda and a gradual tendency of Czech newspapers to relapse into their old ways made it obvious even to a simpleton that the old state of affairs would soon be restored. The danger of a military conflict was all the greater as there was always the possibility that some madman might gain control of those vast stores of war material. This involved the danger of explosions of unforeseeable extent.

As a proof of this, I am constrained, gentlemen, to give you an idea of the truly gigantic extent of this international storehouse of explosives in Central Europe.

Since the occupation of this territory, 23 the following items have been taken over and secured: Air Force: airplanes, 1582; anti-aircraft guns, 501. Army: guns, light and heavy, 2175; trench mortars, 785; tanks, 469; machine guns, 43,876; pistols, 114,000; rifles, 1,090,000. Infantry munitions: more than 1,000,000,000 rounds; Artillery and gas munitions: more than 3,000,000 rounds; All kinds of other war implements, such as, bridge-building equipment, aircraft detectors, searchlights, distance measuring instruments, motor vehicles and special motor vehicles – in large quantities.

I believe that it’s a blessing for millions and millions that, thanks to the last-minute insight of responsible men on the other side, I succeeded in averting such an explosion, and found a solution that, I am convinced, has finally eliminated this problem as a source of danger in Central Europe. The contention that this solution is contrary to the Munich Agreement can neither be justified not supported. Under no circumstances could that Agreement be regarded as final, because it referred itself to other problems that required solution, and which would have to be solved.

We cannot justly be reproached for the fact that the parties concerned – and this is the key point – did not turn to the Four Powers, but only to Italy and Germany, 24 nor for the fact that the state as such finally collapsed of its own accord, and that consequently Czechoslovakia ceased to exist. It was, however, entirely understandable that, long after ethnographic principles had been violated, Germany should take its own measures to protect her thousand-year-old interests, which are not only political but also economic in their nature.

The future will show whether the solution that Germany has found is right or wrong. One thing is certain, however, namely that this solution is not subject to British supervision or criticism. For Bohemia and Moravia, as the remnants of former Czechoslovakia, have nothing more to do with the Munich Agreement. Just as British measures, say in Ireland, 25 whether they be right or wrong, are not subject to German supervision or criticism, the same principle holds good as well for these old German Electorates.

I entirely fail to understand how the agreement reached between Mr. Chamberlain and myself at Munich 26 can apply in this case, for the case of Czechoslovakia was dealt with at the Munich Four Power Conference as far as it could be settled at all at that time. Beyond that, it was only provided that if the interested parties should fail to come to an agreement, they would be entitled to appeal to the Four Powers, who had agreed that in such an eventuality to meet for further consultation after the expiration of three months. However, those interested parties did not appeal to the Four Powers at all, but only to Germany and Italy. That this was fully justified, moreover, is proven by the fact that neither Britain nor France have raised any objections to it, but rather they themselves accepted the arbitration decision made by Germany and Italy.

No, the agreement reached between Mr. Chamberlain and myself had nothing to do with this problem, but solely with questions concerning relations between Britain and Germany. This is clearly shown by the fact that such questions are to be dealt with in the future in the spirit of the Munich Agreement and of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement 27 – that is, in a friendly spirit by way of consultation. If, however, that agreement were to be applied to every future German activity of a political nature, Britain, too, should not take any step – whether in Palestine or elsewhere – without first consulting Germany. It is obvious that we do not expect that; likewise, we reject any similar expectation of us. If Mr. Chamberlain now concludes from this that the Munich Agreement has become invalid because we have broken it, I will note that view and draw the necessary conclusions.

During the whole of my political activity I have always stood for the idea of a close friendship and cooperation between Germany and Britain. In my movement I found countless others of like mind. Perhaps they joined me because of my attitude in this regard. This desire for Anglo-German friendship and cooperation conforms not merely to sentiments based on the [similar] heritage of our two peoples, but also on my realization of the importance of the existence of the British Empire for the whole of humankind.

I have never left any doubt of my belief that the existence of this empire is an inestimable factor of value for the whole of human culture and economic life. By whatever means Great Britain has acquired her colonial territories – and I know that they were those of force and often brutality – nevertheless I am well aware that no other empire has ever come into being in any other way, and that, in the final analysis and from a historical perspective, it is not so much the methods that are taken into account as success, and not the success of the methods as such, but rather the general good that those methods produce.

Now, there is no doubt that the Anglo-Saxon people has accomplished immense colonizing work in the world. For this work I have sincere admiration. The thought of destroying that labor seemed and still seems to me, from the higher point of view of humanity, as nothing but a manifestation of human wanton destructiveness. Yet, my sincere respect for this achievement does not mean that I will neglect to secure the life of my own people.

I regard it as impossible to achieve a lasting friendship between the German and the Anglo-Saxon peoples if the other side does not recognize that just as the preservation of the global British empire is regarded by Britons as a vital purpose and goal, so likewise do Germans regard the freedom and preservation of the German Reich. A genuine lasting friendship between these two nations is conceivable only on a basis of mutual respect.

The British people rule a great global empire. They built up this empire at a time when the German people were internally weak. Germany had once been a great empire. At one time she ruled the Occident. In bloody wars and religious conflicts, and as a result of internal political divisions, that empire declined in power and greatness and finally fell into a deep sleep. But when that old Reich appeared to have reached its end, the seeds of its rebirth were springing up. From Brandenburg and Prussia there arose a new Germany, the Second Reich, and out of it has at last grown the German People’s Reich.

I also hope that all the British understand that we do not possess the slightest feeling of inferiority to Britons. Our historical past is too tremendous for that Britain has given the world many great men, and Germany no less. The severe struggle to maintain the life of our people has, in the course of three centuries, cost a sacrifice in lives that far exceeds that which other peoples have had to make to maintain their existence.

If Germany, a country that was forever being attacked, was not able to hold on to her possessions, but was compelled to sacrifice many of her provinces, that was due solely to her political maldevelopment and the impotence that resulted from it. That condition has now been overcome. Therefore, we Germans do not feel in the least inferior to the British nation. Our self-esteem is just as great as that of an Englishman. The history of our people over almost two thousand years provides events and accomplishments enough to fill us with justifiable pride.

Now, if Britain cannot understand our point of view, thinking perchance that she may regard Germany as a vassal state, then our affection and friendship have indeed been offered in vain. We shall not despair or lose heart on that account, but – relying on the consciousness of our own strength and on the strength of our friends – we shall find ways and means to secure our independence without impairing our dignity.

I have noted the statement of the British Prime Minister to the effect that he is unable to put any trust in German assurances. 28 Under these circumstances I regard it as a matter of course that we should no longer expect him or the British people to accept a situation that has become onerous to them and which is sustainable only on the basis of mutual confidence.

When Germany became National Socialist 29 and thus paved the way for her national resurrection, in pursuance of my unswerving policy of friendship with Britain, of my own accord I made a proposal for a voluntary restriction of German naval armaments. 30 That restriction was, however, based on one condition, namely the will and the conviction that a war between Britain and Germany would never again be possible. That will and that conviction I still hold today.

Now, however, I am compelled to state that the policy of Britain, both unofficially and officially, permits no doubt that such a conviction is no longer shared in London, and that, on the contrary, the opinion prevails there that no matter in what conflict Germany might one day be entangled, Great Britain will always have to stand against Germany. Thus war against Germany is more or less taken for granted there.

I most profoundly regret such a development, for the only claim I have ever made and shall continue to make of Britain is for the return of our colonies. But I always made it very clear that this would never become a cause of military conflict. I have always held that the British, for whom those colonies are of no value, would one day understand the German situation, and would then value German friendship higher than the possession of territories that, while yielding no real profit whatever to them, are of vital importance for Germany.

Apart from that, however, I have never advanced a claim that might in any way have interfered with British interests, or that might become a danger to the Empire, and thus might mean any harm for Britain. I have always made sure that such demands as have been made have always been closely connected with Germany’s vital territory, and with the inalienable property of the German nation.

Now that Britain, both in the press and officially, now expresses the view that Germany should be opposed under all circumstances, and confirms this through the well-known policy of encirclement, the basis for the [1935] Naval Treaty has been removed. I have therefore resolved to send today a communication to that effect to the British government.

This is to us not a matter of practical material importance – for I still hope that we shall be able to avoid an armaments race with Britain – but rather a matter of self-respect. If the British government, however, wishes to enter once more into negotiations with Germany on this problem, no one would be happier than I at the prospect of being able, after all, to come to a clear and straightforward understanding. Moreover, I know my people, and I rely on them. We do not want anything that did not formerly belong to us, and no state will ever be robbed by us of its property; but anyone who believes that he is able to attack Germany will find himself confronted with a measure of power and resistance compared with which that of 1914 was negligible.

In connection with that I wish to speak here and now of that matter that was chosen as the starting-point for the new campaign against the Reich by those same circles that caused the mobilization of Czechoslovakia. I have already assured you, gentlemen, at the beginning of my speech, that never, either in the case of Austria or in the case of Czechoslovakia, have I adopted any attitude in my political life that is not compatible with events that have now happened. I therefore pointed out in connection with the problem of the Memel Germans that this question, if it was not solved by Lithuania itself in a dignified and generous manner, would one day have to be raised by Germany.

You know that the Memel territory was also once torn from the Reich quite arbitrarily by the Dictate of Versailles and that finally, in the year 1923 – that is to say, in the midst of a period of complete peace – that territory was occupied by Lithuania, and thus more or less confiscated. The fate of the Germans has since then been sheer martyrdom.

In the course of reincorporating Bohemia and Moravia within the framework of the German Reich it was also possible for me to come to an agreement with the Lithuanian government that allowed the return of that territory to Germany without any act of violence and without shedding blood. 31 In this instance as well, I have not demanded one square mile more than we formerly possessed, but which had been stolen from us.

This means, therefore, only that a territory has returned to the German Reich which had been torn from us by the madmen who dictated peace at Versailles. But this solution, I am convinced, will only prove advantageous with regard to relations between Germany and Lithuania. That’s because Germany, as our attitude has proved, has no other interest than to live in peace and friendship with that country, and to establish and foster economic relations with it.