Canada A Country Without A Constitution: A Factual Examination Of The Constitutional Problem

Source: http://historylessonsdeleted.blogspot.com/2019/03/canada-country-without-constitution.html

by: Walter F. Kuhl, Member of Parliament Jasper-Edson 1935-1949 | Published: January 1977

"It is therefore easy to see why Canada is not a confederation............."

Dr. Maurice Ollivier, K.C., Joint Law Clerk, House of Commons, before the Special Committee on the British North America Act, 1935

"I have always contended, for reasons too long to enumerate here, that it [Canada] has not become either a confederation or a federal union."

Dr. Ollivier, in a personal letter to Mr. Kuhl, May 30th, 1936

Forward

There is probably no political issue in Canada on which there is more lack of information and more misinformation than on the constitutional question. The stalemate and the impasse which the governing authorities in Canada have reached on this question seem to indicate that there is and has been something very fundamentally awry in Canada's constitutional history.

For almost half a century this controversy has been raging without a satisfactory solution having been arrived at. Many Canadians, myself included, have had enough of this bickering between politicians and are determined to do something to bring this internecine strife to an end.

The purpose of this booklet is to indicate in some measure what I as a member of the House of Commons and as a private citizen have attempted to do to bring order out of the constitutional chaos in which Canada finds herself. Democracy is successful only in proportion to the knowledge which people have with respect to their rights and privileges. It is my hope that the information contained in this brochure will assist Canadians to that end.

Immediately following the recent Quebec election, I sent to Mr. Rene Levesque a personal letter in which I indicated my conception of the constitutional rights which the provinces of Canada enjoy at the moment. At the conclusion of this booklet will he found a reproduction of this letter. Included with this letter was the additional material found in this booklet. A copy of my letter to Mr. Levesque, along with copies of the additional material, was subsequently mailed to each of the premiers of the provinces of Canada.

I desire to express my gratitude to Mr. R. Rogers Smith, who as my private tutor for almost the entire fourteen years during which I served as a member of the house of Commons, brought to my attention facts from the statutes at large, from the Archives and from original historical sources, the material upon which this brochure is based.

Walter F. Kuhl

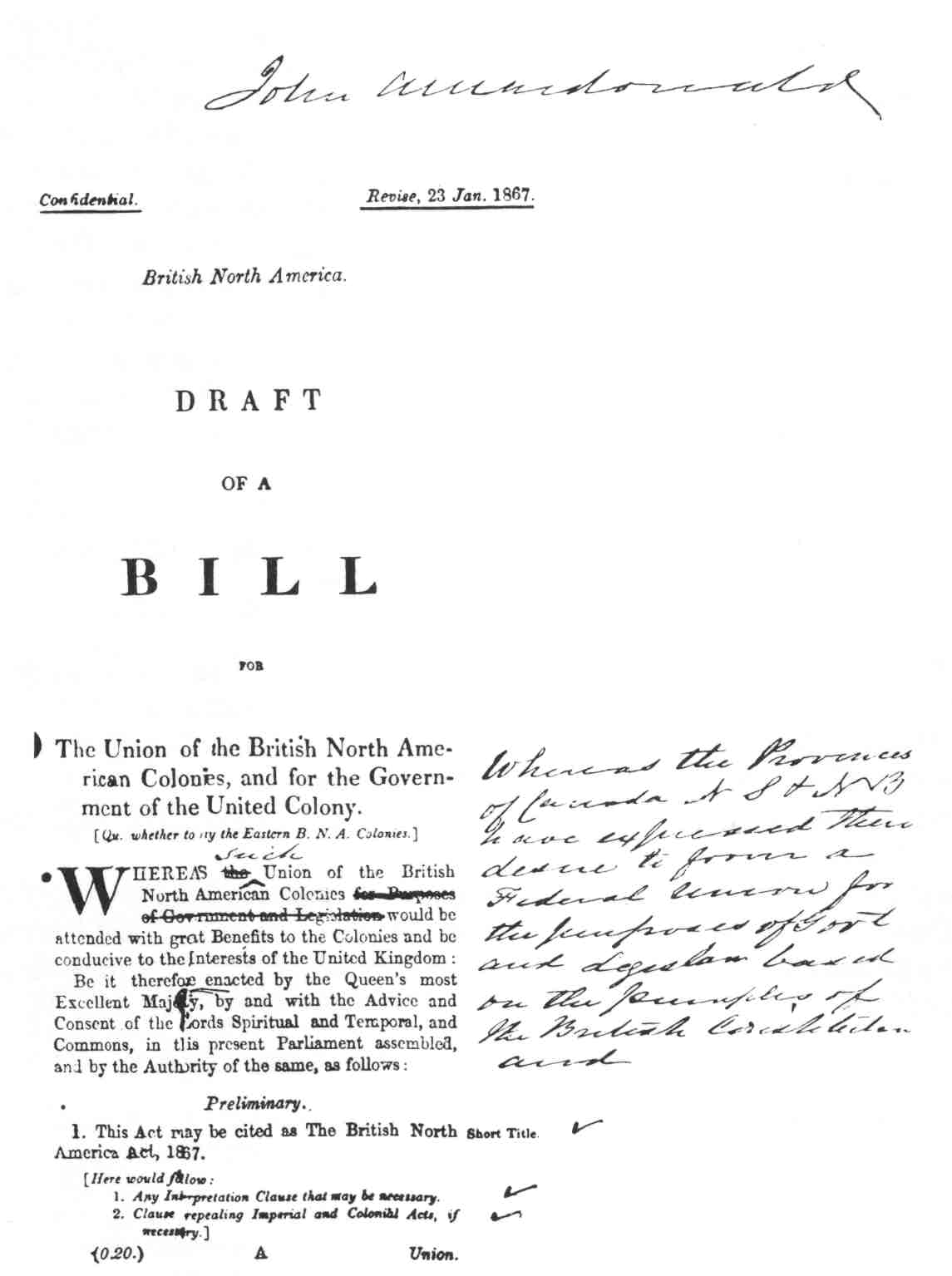

Copy of the first page of the BNA Act (1867). This page was not part of that private members bill that was passed by the British Parliament

On the left is the preliminary draft by the Colonial Office. This means the Domination of the Colony, or the uniting of the Colonies into one Dominion. This is the basis of the British North American Act.

Notice how they stroked out "for the purposes of Government and Legislation", and left the emphasis on "colonies"

On the right is the desire of the Provinces to unite into a Federal Union; which means freedom. Drafted by John A. MacDonald before he received his title. One draft is diametrically opposed to the other. The hand written text:

This is a copy of a page from "Inside Canada", a publication by R. Roger Smith.

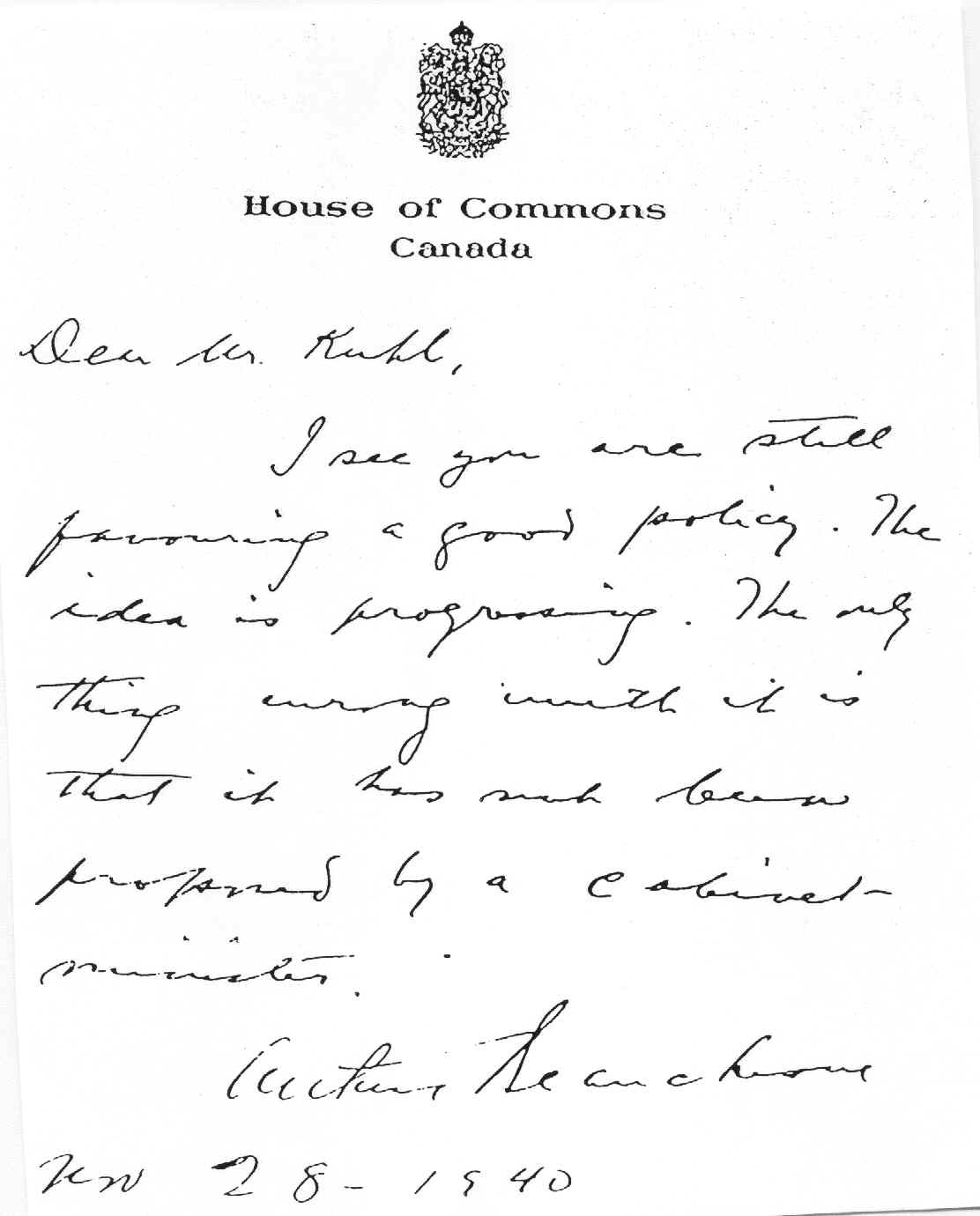

Memo of support from Dr. Beauchesne, Parliamentary Secretary

Text:

Dr. A. Beauchesne']

['Dated: June 28, 1940. and sent in response to a speech made by Mr. Kuhl on Canadian constitutional problems on June 25th, 1940.

Confederation A Myth by Elmer Knutson

Author of: Confederation or Western Independence

In my search for truth, I found several handwritten articles, written in very large script by Lord Monck on sheets of paper 11 x 14. As that is much larger than the pages of this book I have reduced them in size, which makes them unreadable without a magnifying glass. So I have typed the contents of each page for your convenience.Lord Monck was the Governor of Quebec, and he also became the first Governor General of Canada. He sat in on all the discussions during the Quebec Conference of 1864, he knew what the drafters of the Quebec resolutions intended and wanted, and as such was intimately acquainted with the thoughts and wishes of the delegation which went to London in December 1866. He reported in the first six pages of his dispatch his personal observations of the "scheme" to his superior the Right Honorable Edward Cardwell M.P. in charge of the Colonial department, the eventual author of the B.N.A. Act.

Lord Monck's Letter

Confidential

25NOV64 Government House

Quebec

Nov. 7,1864

The Right Honourable Edward Cardwell M.P.

Sir,

In another dispatch of this date I have had the honour of transmitting to you the resolutions adopted by the representatives of the different colonies of British North America at their late meeting at Quebec in reference to the proposed Union of the Provinces.

I propose in this dispatch to lay before you some observations of my own on the proposed scheme which I think it would be judicious for the present at least, to treat as confidential.

I must in the first place express my regret that the term "Confederation" was ever used in connection with the proposed Union of the British North American Provinces both because I think it an entire misapplication of the term and still more because I think the word is calculated to give a false notion of the sort of union which is desired. I might almost say which is possible, between the provinces.

A Confederation or Federal Union as I understand it, means a union of Independent Communities bound together for certain defined purposes by a treaty or agreement entered into in their quality of sovereign states, by which they give up to the central or federal authority for those purposes a certain portion of their sovereign rights retaining all other powers not expressly delegated in as ample a manner as if the Federation had never been formed.

If this be a fair definition of the term Federation and I think it is applicable to all those Federal Unions of which history gives us examples, it is plain that a Union of this sort could not take place between the provinces of British North America, because they do not possess the qualities which are essential to the basis of such a union.

They are in no sense sovereign or independent communities.

They possess no constitutional rights except those which are expressly conferred upon them by an Imperial Act of Parliament and the power of making treaties of any sort between themselves is not one of those rights.

The only manner in which a Union between them could be effected would be by means of an act of the Imperial Parliament which would accurately define the nature of the connection, and the extent of the respective powers of the central and local authorities, should any sort of union short of an absolute Legislative Consolidation be decided on. (Elmer's note: the BNA Act was just that)

The Sovereignty would still reside in the British Crown and Imperial Legislature, and in the event of any collision of authority between central and local bodies there would be the power of appeal to the supreme tribunal from which all the colonial franchises were originally derived and which would possess the right to receive the appeal, the authority to decide, and the power to enforce the decision.

A Distinctive National Flag And Constitutional Problems In Canada

Delivered in the House of Commons on Thursday, November 08, 1945

Mr. W. F. KUHL (Jasper-Edson): This resolution urges the expediency of Canada's possessing a distinctive national flag. I agree that an anomaly exists with respect to the matter of a Canadian flag, and I, and my associates in parliament are in favour of removing this condition. But personally I consider that under the constitutional conditions prevailing in this country at the moment such action is premature. There are other and more important actions to be taken before it is appropriate to adopt a new flag.

The flag question is just one of the many anomalies which exist in Canada's constitutional position. Some of these have' been referred to this afternoon. One of them, the matter of Canadian citizenship, is intended to be dealt with at this session. There are others, such as amendments to the constitution, appeals to the privy council, the power of disallowance, the matter of a federal district proper - and doubtless there are others. All these anomalies ought to be dealt with, and I am personally in favour of dealing with them at the earliest possible opportunity. But I consider that the present piecemeal method is improper as well as undemocratic. I contend that the people of Canada are not being consulted in the manner in which I believe they ought to be concerning their rights in these questions.

To Account For Anomalies

I wish to indicate, Mr. Speaker, my reasons for contending that the method that is proposed to attempt to remove these anomalies is improper and undemocratic. Then I wish to indicate what I consider to be the proper method to use. To do this I first wish to endeavor to, account for the constitutional circumstances in which we find ourselves at the moment.

The question which must occur to every hon. member of this house and to every other citizen in this country is, why do such anomalies exist in our constitutional position? How did they come about? There must be something in Canada's constitutional history that accounts for the circumstances in which we find ourselves. No other part of the British Empire finds itself in the same circumstances. Why are these conditions peculiar to the people of Canada? In endeavoring to answer these questions, and in suggesting what I consider to be the proper remedy for them, I am not posing as a constitutional expert, although I may say it is now ten years since I began my studies on this subject, and I trust, I shall not be considered presumptuous in claiming to have added a little to my knowledge in that time.

The matters which I wish to discuss are those with which every public school child in the seventh and eighth grades, every high school student, and certainly every voter, should be thoroughly familiar. Every citizen in the land should know by what authority we do things in this country. On several occasions during the past two parliaments I have argued the case I am about to introduce, but very little attention was paid to my statements either in the house or out of it. On this occasion I intend to be heard, and if not, I demand to know the reason why. I consider that the situation which I shall discuss is of such importance that a reply or a comment should certainly be forthcoming from the Acting Prime Minister (Mr. Ilsley) the Minister of Justice (Mr. St. Lauremt), and for that matter, from all hon. members of the house. I and the people who have sent me here have a right to know whether there is, or is not, a basis in fact for my contentions, and if there is, they have the right to know what is going to be done about it.

Submit Reasoned Argument

I propose to make a reasoned argument supported by the best evidence I have been able to secure. If my argument is to be controverted, I demand that it be met with a reasoned argument and not with personal abuse and statements which are wholly irrelevant. I expect a more intelligent criticism of my argument than was exhibited by a certain hon. member when I discussed this subject in a previous parliament. In Hansard of April 8, 1938, at page 2183, this little exchange took place between myself and the hon. member for Selkirk, Mr. Thorson:

Mr. MacNicol: He has queer ideas of his own.

Mr. Kuhl: I continue:

Mr. Thorson: Why battle against windmills.

I submit that the subject matter and the arguments which I presented on that occasion were worthy of more intelligent criticism than was exhibited by that hon. gentleman. I have long ago learned that when an individual has a weak argument, or no argument at a1l, he usually resorts to personal abuse of his opponent. If hon. members have not a better argument to make than Mr. Thorson made on that occasion, I suggest that they hold their peace.

In submitting my argument, Mr. Speaker, I wish to assure you that I am actuated by the highest possible motives. We proudly proclaim our faith in democracy; we proclaim it from the housetops. I wish to urge that we practice what we preach. Let us demonstrate democracy instead of merely paying lip service to it.

It is my desire to see the people of Canada consulted where their fundamental rights are concerned. I wish to see government of the people by the people. These are the motives which actuate me in what I have to say on this resolution.

In presenting the special case I am about to discuss I am not necessarily speaking as a member of the Social Credit group; I am speaking as a native of Canada. The matters on which I am to speak are of fundamental concern to every citizen of Canada regardless of his or her political persuasion. They are among the most serious matters upon which a citizen can be called to think; they are the bed-rock considerations of human government.

I submit that the subject matter and the arguments which I presented on that occasion were worthy of more intelligent criticism than was exhibited by that hon. gentleman. I have long ago learned that when an individual has a weak argument, or no argument at a1l, he usually resorts to personal abuse of his opponent. If hon. members have not a better argument to make than Mr. Thorson made on that occasion, I suggest that they hold their peace.

In submitting my argument, Mr. Speaker, I wish to assure you that I am actuated by the highest possible motives. We proudly proclaim our faith in democracy; we proclaim it from the housetops. I wish to urge that we practice what we preach. Let us demonstrate democracy instead of merely paying lip service to it.

It is my desire to see the people of Canada consulted where their fundamental rights are concerned. I wish to see government of the people by the people. These are the motives which actuate me in what I have to say on this resolution.

In presenting the special case I am about to discuss I am not necessarily speaking as a member of the Social Credit group; I am speaking as a native of Canada. The matters on which I am to speak are of fundamental concern to every citizen of Canada regardless of his or her political persuasion. They are among the most serious matters upon which a citizen can be called to think; they are the bed-rock considerations of human government.

Basic Premises

In order to endeavor to account for the contradictions in Canada's constitutional position and to suggest a remedy therefor, I wish to lay down some fundamental premises on which I shall base my entire argument. Locke is credited with saying:

Jefferson, in the declaration of independence states:

Federal Union Defined

In addition to that promise, I wish to indicate the definition of a federal union. What is a federal union? Bouvier in his law dictionary defines "federal government" as:

Doctor Ollivier, joint law clerk of the House of Commons, on page 85 of the report of the special committee on the British North America Act, said:

A. P. Newton, in his book entitled "Federal and Unified Constitutions," at page 5 says:

Two points stand out prominently in these definitions. The first is that the states which form the union must be sovereign, free and independent before they federate; the second, that the federal constitution which forms the basis of the union must be accepted by the citizens of the federating states. I think it worth while in this connection to point out that when the states of Australia federated, the people of Australia were provided with two opportunities of voting on their constitution. I should like to quote a paragraph from a history of the Australian constitution by Quick and Garran. This paragraph is on the meaning of the words "have agreed" in the constitution, and it states:

In this manner, there was, in four colonies, a popular initiative and finally in all the colonies a popular ratification of the constitution, which is thus legally the work, as it will be for all time, the heritage of the Australian people. This democratic method of establishing a new form of government may be contrasted with the circumstances and conditions under which other federal constitutions became law.

Federal Union Desired In 1867

Now I should like to ask a few questions concerning our position in Canada. Did the provinces of Canada desire federal union? The Quebec resolutions, the London resolutions, and the draft of the bill by the London delegates all indicate that the provinces of Canada desired federal union. The preamble to the Quebec resolutions reads:

Clause 70 of the Quebec resolutions indicates that whatever agreement was arrived at by the delegates would be submitted to the provinces for their approval. It reads:

Furthermore, a bill drafted in London by the Canadian delegates contains the same preamble that appears in the Quebec resolutions, and this draft bill also contains a repealing clause which hon. members can find on page 179 of Pope's "Confederation Documents". It reads:

Canada Not Federated Under B.N.A. Act

The next question is: Did Canada become a federal union under the British North America Act. I submit that the manner in which the bill was drafted and the manner in which it was enacted throw much light on the answer to this question. The act was drafted by the law officers of the Crown attached to the colonial office. Lord Carnarvon, Secretary of State for the colonies, was the chairman of the conference. Sir Frederick Rogers, Under-secretary for the colonies, in Lord Blachford's Letters, is quoted as saying at page 301:

In reading accounts of the times, it is quite obvious that the bill which was drafted by the colonial office seems to have prevailed over that which was drafted by the delegate from Canada. The title and preamble of the bill drafted by the Colonial Office read:

That is the preamble of the draft bill submitted by the colonial office, whereas the preamble of the bill drafted by the Canadian delegates read:

I submit, Mr. Speaker, no evidence is to be found to show that the preamble which we find in the printed copies of the British North America Act in Canada was either discussed or proven in the British Parliament. This preamble reads:

Lord Carnarvon, who introduced the bill on February 19, 1867, used these words as reported at page 559 of the British Hansard:

Furthermore Lord Campbell, speaking to the bill on February 26 of the same year, is reported at page 1012 of the British Hansard as having said:

I submit it should be evident from these quotations that the preamble which was discussed was that to be found in the Quebec resolutions, not the one we find in the printed copies of the British North America Act in Canada.

A pertinent question to ask at this point would be: When was the present preamble placed in the British North America Act? Why was it not discussed in the British Parliament, and, furthermore, what is the significance of an act bearing a preamble which was not even discussed, let alone proven? Another point of significance in connection with this, I believe, is the undue haste with which the bill was passed through the Imperial Parliament. When second reading was called for, the bill was not even printed. At page 1090 of British Hansard for February 27, 1867, we find these words:

Mr. Hatfield said he rose to ask the government why it was the second reading of this bill had been fixed for to-morrow. It was one which affected 4,000,000 of people, and upon which great doubts and differences of opinion were entertained. It was not yet printed and was of so important a character that he thought some little time ought to elapse after it was in the hands of the members before it was introduced in order that some little consultation should take place upon it. He was not at all sure that he should be opposed to it, but he certainly required more time to consider it.

Later, on page 1195, on February 28, we find this:

Another significant statement is that by John Bright, which we find at page 1181 of British Hansard for February 28, 1867, as follows:

Conclusions

- The provinces of Canada desired a federal union.

- The Quebec resolutions provided for a federal union.

- The bill drafted by the Canadian delegates at the London conference, also provided for a federal union,

- The colonial office was not disposed to grant the provinces of Canada their request for a federal union.

- The British North America Act, enacted by the Imperial Parliament, carried out neither the spirit nor the terms of the Quebec resolutions.

- Canada did not become a federal union under the British North America Act, but rather a united colony. The privilege of federating, therefore, was still a future privilege.

- The Parliament of Canada did not become the government of Canada, much less a federal government. It became merely the central legislature of a united colony, a legislative body whose only power was that of aiding and advising the Governor General as agent of the Imperial Parliament.

- The British North America Act, as enacted by the Imperial Parliament, was not a constitution, but merely an Act of the Imperial Parliament which united four colonies in Canada into one colony with the supreme authority still remaining in the hands of the British government.

Further Evidence

As further evidence that the British North America Act was not a constitution, and that Canada did not become a federal union, I refer to the definition of the term "dominion" which is to be found in section 18, paragraph 3 of the Interpretation Act of 1889. It reads as follows:

Excepting Canada, no country in the empire had a central legislature and local legislatures. Therefore, according to this definition made twenty-two years after the enactment of the British North America Act, Canada is deemed to be one colony.

To show that I am not alone in my conclusions I quote some of the statements of recognized Canadian constitutional authorities before the special committee on the British North America Act in 1935.

Doctor W. P. M. Kennedy, Professor of Law in the University of Toronto, at page 69 of the report states:

Professor N. McL. Rogers, of Queen's University, at page 115 of the report states in reply to a question by Mr. Cowan:

Mr. Rogers: I am thoroughly convinced it is not, either in the historical or the legal sense.

Then I would quote Doctor Beauchesne, Clerk of the House of Commons, who at page 125 states.

The evidence which I have submitted establishes to my satisfaction that there has been at no time in Canada any agreement, pact or treaty between the provinces creating a federal union and a federal government. The privilege to federate therefore was still a future privilege for the provinces of Canada.

Provinces Completely Sovereign

Since the condition of sovereignty and independence must be enjoyed by the Provinces before they can federate, it was necessary that the British government relinquish its authority over them. This was done through the enactment of the Statute of Westminster on December 11, 1931. By section 7, paragraph 2, of this statute, the Provinces of Canada were made sovereign, free and independent in order that they might consummate the federal union which they wished to create in 1867, but were not permitted to do so.

Since December 11, 1931, the Provinces of Canada have not acted on their newly acquired status; they have not signed any agreement, they have not adopted a constitution, and the people of Canada have not ratified a constitution. Such action should have been taken immediately upon the enactment of the Statute of Westminster. It is by reason of the failure of the Provinces and of the people of Canada to take this action that all the anomalies in our present position exist. We have been trying since 1931 to govern ourselves federally, under an instrument which was nothing more than an act of the Imperial Parliament for the purpose of governing a colonial possession.

Not only has this anomalous condition obtained since 1931, but it has done so without any reference whatsoever having been made to the Canadian people. They have not been consulted on anything pertaining to constitutional matters. Before there can be a federal union in Canada and a federal government, the Provinces of Canada must be free and independent to consummate such a union. They have been free to do so since December 11, 1931, but they have not done so.

Canada Without A Constitution

I therefore pose this question: Whence does the Dominion Parliament derive its authority to govern this country? The Imperial Parliament cannot create a federal union in Canada or constitute a federal government for the people of Canada by virtue of the British North America Act or any other act. This can be done only by the people of Canada, and they have not yet done so.

Since December 11, 1931, as an individual citizen of this country I have had the right to be consulted on the matter of a constitution. I have had the right along with my fellow citizens to ratify or to refuse to ratify a constitution, but I have not been consulted in any way whatsoever. I assert therefore that until I, along with a majority of Canadians, ratify a constitution in Canada, there can be no constitution, and I challenge successful contradiction of that proposition.

Mr. JOHNSTON: Were you?

Mr. POULIOT: No.

Mr. KUHL: I have already answered that. I have indicated the position of the British North America Act, and have pointed out that it has not been accepted as a constitution by the people of Canada.

Mr. KUHL: Yes.

Mr. KUHL: Which one?

Mr. KUHL: Just exactly as I have said, there can be no constitution in Canada, whether it is on the basis of the British North America Act or any other act, until the people of Canada accept it. They have not accepted it.

Mr. KUHL: That does not alter the situation.

Mr. JAENICKE: What are you going to do about it?

Remedy For Condition

Legally, Canada is in a state of anarchy, and has been so since December 11, 1931. All power to govern in Canada since the enactment of the Statute of Westminster has resided with the provinces of Canada, and all power legally remains there until such time as the provinces sign an agreement and ratify a constitution; whereby, they delegate such powers as they desire upon a central government of their own creation. Since December 11, 1931, the Parliament of Canada has governed Canada on assumed power only. It is imperative that this situation be dealt with in a fundamental way. Patchwork methods will not suffice.

Obviously the first act is that the provinces of Canada shall sign an agreement authorizing the present parliament to function as a provisional government. That is number one in answer to my hon. friend. Secondly, steps must then be taken to organize and elect a constituent assembly whose purpose will be to draft a constitution which must later be agreed to by the provinces and then ratified by the people of Canada. The dominion-provincial conference is to reconvene in the near future. This would be a most appropriate time and a most appropriate occasion on which to initiate action of this kind. I trust that the delegates to this conference will not disappoint us in this matter. I shall observe with much interest what will be said in this conference on constitutional relationships in Canada.

Proposals Endorsed

To show that I am not alone in my proposal I quote Doctor Beauchesne from the evidence of the special committee on the British North America Act in 1935. On page 126 of the evidence he is credited with saying:

And on page 128 Doctor Beauchesne is reported as follows:

And again on page 131:

And page 135:

And finally on page 129:

I should also like to quote in this connection a resolution which was adopted at a convention of Social Credit supporters and monetary-reform-minded people held in the city of Edmonton in 1942. This resolution is to be found at page 59 in the publication "Prepare Now," issued by the Bureau of Information, Legislative Building, Edmonton. It reads as follows:

- The existing legislative and administrative organisation in the provincial and federal spheres.

- A more expedient allocation of powers as between the provincial and federal authorities.

- Ways and means of facilitating the drafting, the adoption and the implementation of a Canadian constitution in keeping with the rights granted in the Statute of Westminster.

I contend, Mr. Speaker, that such are the actions which should be taken before it is appropriate to adopt a distinctive national flag. I submit that the adoption of a new flag of our own designing should be the crowning act to putting our constitutional house in order.

I believe that the statements which I have placed upon the record are historical facts. I believe that the conclusions which I have drawn from these facts are the only ones which can be drawn from them, and I believe, consequently, that the solution which I have suggested is the only one adequate for the circumstances. If hon. members of this assembly can successfully dispute either the facts which I have submitted or the conclusions which I have drawn therefrom, I shall be prepared to withdraw those conclusions, but if they do not do so, I believe the people of the country have a right to know what they propose to do in the circumstances.

It was my intention to move an amendment, but as one has been moved already I shall refrain from doing so until the amendment already moved has been dealt with. So far as the substance of that amendment is concerned, I repeat what I have previously indicated. I think it is premature to consider any flag, either the one suggested in the amendment or any other. There are other and more important actions to be taken before we can consider the adoption of a new flag.

Explanation Of The Statue of Westminister

Ottawa: Printed by Edmond Cloutier, Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty, 1945

The Parliament of a Dominion in Section 2 does not refer to the legislative body sitting in Ottawa on December 10, 1931. The legislative body sitting in Ottawa the day before the Statute of Westminster was passed, according to the Interpretations Act of 1889, Sec. 18, Par. 3, was the Central Legislature of a United Colony, whose only function and authority was to aid and advise the Governor General as the agent of the British Government.

Section 2 does not validate the Central Legislature of a United Colony as the Federal parliament of a Federal Union. A Federal Union in Canada can be created only by completely independent and autonomous provinces, which section 7 (2) provides for.

As a consequence of Section 11, the term, Dominion, can now be applied to a Federal Union, and the term, the Parliament of a Dominion can now be applied to a Federal Parliament and not be inconsistent insofar as a definition is concerned. However, the British Government can no more convert the Central Legislature of a United Colony into the Federal Parliament of a Federal Union, by changing definitions, than it can turn water into wine.

The only validity which the B.N.A. Act has since December 11, 1931, is as a guide to the creation of a Federal Union which only the provinces can bring about. The provinces of Canada are free to use it as a guide in the creation of a Federal constitution, or they may reject it completely in favour of a constitution of their own making.

As an analogy, it might be said that the relationship into which the original provinces entered under the B.N.A. Act was a sort of shot-gun marriage; they were forced into a United Colony against their will. The Statute of Westminster gave the provinces their independence so that they could consummate a voluntary marriage, but they have not yet done so. Ever since December 11, 1931, the provinces have been living common-law with Ottawa and have the right to terminate this arrangement at any time they wish.

End

Pertinent Clauses From The Statue Of Westminister And Their Statues

- 2. (1) The Colonial Laws Validity Act. 1865, shall not apply to any law made after the commencement of this Act by the Parliament of a Dominion.

- (2 ) No law and no provision of any law made after the commencement of this Act by the Parliament of a Dominion shall he void or inoperative on the ground that it is repugnant to the law of England, or to the provisions of any existing or future Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom, or to any order, rule or regulation made under any such Act, and the powers of the Parliament of a Dominion shall include the power to repeal or amend any such Act, order, rule or regulation in so far as the same is part of the law of the Dominion.

- 4. No Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom passed after the commencement of this Act shall extend or be deemed to extend, to a Dominion as part of the law of that Dominion, unless it is expressly declared in that Act that that Dominion has requested, and consented to, the enactment thereof.

- 7. (1) Nothing in this Act shall be deemed to apply to the repeal, amendment or alteration of the British North America Acts, 1867 to 1930, or any order, rule or regulation made thereunder.

- (2) The provisions of section two of this Act shill extend to laws made by any of the Provinces of Canada and to the powers of the legislatures of such Provinces.(3) The powers conferred by this Act upon the Parliament of Canada or upon the legislatures of the Provinces shall he restricted to the enactment of laws in relation to matters within the competence of the Parliament of Canada or of any of the legislatures of the Provinces respectively.

- 11. Notwithstanding anything in the Interpretation Act, 1889, the expression "Colony" shall not, in any Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed after the commencement of this Act, include a Dominion or any Province or State forming part of a Dominion.

THE INTERPRETATIONS ACT, 1889

Sec. 18, Par. 3, - The expression "Colony" shall mean any of Her Majesty's Dominions exclusive of the British Islands and British India, and where parts of such dominions are under both a Central Legislature and Local Legislature for the purposes of this definition shall be deemed to be one Colony.

THE COLONIAL LAWS VALIDITY ACT, JUNE 29th, 1865.

Sec. 6, - Any proclamation purported to be published by the authority of the Governor, circulating in any newspaper in the Colonies, signifying Herr Majesty's assent to any Colonial law or Her Majesty's disallowance of any such reserved bill as aforesaid, shall be prima facie evidence of such disallowance or assent.

Letter to The Honourable Rene Levesque

Spruce Grove, Alta., R.R. I,

November 23rd, 1976.The Hon. Rene Levesque,

Premier-elect,

Province of Quebec,

Quebec, P.Q.

Dear Mr. Levesque:

Congratulations on your magnificent personal victory and that of your Parti Quebecois in the recent Quebec election.

As a student of Canadian constitutional history and of Canadian constitutional problems for some 40 years, I am tremendously interested in the constitutional implications of your recent political victory. For 14 years, from 1935 to 1949, it was my privilege to serve as a member of the House of Commons, from the province of Alberta. The withholding of assent to some Alberta legislation in those years by the Lieutenant-Governor and the dis-allowance of other Alberta legislation by the people at Ottawa, set me to investigating how these things could be.

I was assisted in my studies by R. Rogers Smith, who was personally acquainted with a onetime private secretary to John A. MacDonaId at the time when the B.N.A. Act was being enacted. Through this source I have become acquainted with much information concerning the history of the B.N.A. Act which is not to be found in text books.

All this information has led me to the conclusion that the existing constitutional circumstances are shocking to the point of unbelief. However, in my considered opinion, after 40 years of intensive study, these existing constitutional circumstances are of such a nature that they can be of extreme advantage to you in governing your province.

I am enclosing copies of some of the addresses which I delivered in the House of Commons on the subject, as well as copies of a pamphlet by Mr. Smith, dealing with the same subject. If you have not already been made acquainted with this material, I trust it will prove enlightening and helpful to you in the constitutional considerations in which you obviously are going to become involved.

Although the enclosed material should give you a clear outline of what I conceive to be your present standing constitutionally as a province, 1 would like to give you a brief summary of what I believe to be your present position.

So far as separation. is concerned, rather than it being necessary to seek separation rights through a referendum, THE PROVINCE OF QUEBEC IS ALREADY COMPLETELY CONSTITUTIONALLY SEPARATED FROM THE REST OF CANADA ! ! ! ! This is equally true of every other province in Canada and has been so since December 11, 1931, through the Statute of Westminster.

HOW CAN YOU BE DIVORCED IF YOU HAVE NEVER BEEN MARRIED?

In other words, ever since the enactment of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, by the British Govemment, each of the provinces of Canada has been a completely sovereign and independent state, and because the provinces have signed nothing since then constituting a Federal Union and a Federal Government, and because no such treaty has been ratified by the people of Canada, the provinces still enjoy the status of sovereignty and are privileged to use it in any way they see fit.

As you will observe from the enclosed addresses, I quote eminent Canadian constitutional authorities as suggesting that the only and logical solution to the existing constitutional circumstances is the drafting and the adoption of a proper federal constitution in which the provinces can reserve for themselves any and all powers necessary to enable them to govern their provinces successfully.

I am sure you can appreciate that if this were done, you could solve your economic and other problems in Quebec without resorting to separation. I feel sure that having the ability to solve your problems and still remain constitutionally part of the country of Canada, would be much more satisfactory to your supporters as well as to others within your province.

The following is a summary of the reasons for the things I have just stated:

- At the time of Confederation movement in Canada, the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick desired to form a Federal Union.

- The Quebec Resolutions of 1864 provided for a Federal Union.

- The Bill drafted by the Canadian degates at the London Conference in 1866 also provided for a Federal Union.

- The Colonial Office of the Imperial Parliament was not disposed to grant the Provinces of Canada their request for a Federal Union.

- The British North America Act enacted by the Imperial Parliament carried out neither the spirit nor the terms of the Quebec Resolutions.

- Canada did not become a Federal Union or a Confederation under the British North America Act, but rather a United Colony. The privilege of federation, therefore, was still a future privilege for the provinces of Canada.

- The Parliament of Canada did not become the government of Canada, much less a federal government; it became merely the central legislature of a United Colony, a legislative body whose only power was that of aiding and advising the Governor-General as agent of the Imperial Parliament.

- The British North America Act, as enacted by the Imperial Parliament, was not a constitution but merely an act of the Imperial Parliament which united four colonies in Canada into one colony, with the supreme authority still remaining in the hands of the British government.

- The privilege of federating became realizable for the provinces of Canada, only through the enactment of the Statute of Westminster on December 11, 1931. Through this statute, the Imperial Parliament relinquished to the people of Canada their sovereign rights, and through them to their Provincial governments as their most direct agents.

- Since December 11, 1931, the Provinces of Canada have not acted on their newly acquired status in the forming of a Federal Union, nor have the people of Canada ratified a constitution. Therefore, the original proposition, namely: that all power to govern in Canada resides at the moment, with the Provinces of Canada; and, that all power legally remains there until such time as the Provinces sign an agreement and ratify a constitution whereby they may delegate such powers as they wish to a central government of their own creation. In the meantime, Canada exists as ten political units without a political superior.

Should you consider that there is merit in the information which I have given you, I would be very happy to meet with you personally to discuss in greater depth the implications of the unprecedented constitutional circumstances prevailing in Canada.

Yours for a better Canada,

Walter F. Kuhl

Member of Parliament for Jasper-Edson, 1935-1949

Note From The Source Page

An added note on the question: What right or authority does the Queen of Great Britain have in calling herself the Queen of Canada? What right does she have in being the plaintiff in charges made in the name of the Crown against any man or woman living on the landmass called Canada?

The Canadian Governor General's website has, and probably still does, point out that the office of Governor General is 'de facto', which in referring to government means that authority has been unlawfully usurped (assumed). It is interesting that the Criminal Code of Canada, (belonging to the de facto government of Canada), says in Section 15 that laws of a de facto government carry no liability for non-compliance.The BNA Act (1867) section 2: The provisions of this Act referring to Her majesty the Queen extends also the the heirs and successors of Her Majesty, Kings and Queens of the United Kingdom of Great britain and Ireland. The Imperial Parliament repealed section 2 of the BNA Act (1867) by the Statutes Revision Act of 1893. Under what authority did the successor to Queen Victoria, or successors to the British throne since, continue to rule Canada as the Crown of Canada?

Where is the "CROWN OF CANADA"???? Where is the "THRONE OF CANADA"????

Related: The Myth Is Canada

Tags: Canada, Constitution, Law, BritishEmpire

This page may have a talk page?.

Access and use of this site by any means implies consent to the Agreement of Use. © Hellene Sun